Which Assessment Finding Indicates That The Infant Has Hypotensive Shock

Table of contents will be automatically generated here...

Introduction

In the primary survey, circulation becomes the priority later airway and breathing have been definitively managed. Delivery ofoxygen to the tissues is dependent on adequate circulation. In this affiliate, differences betwixt adults and children are discussed followed by a review of circulatory compromise and its definitive management.

How are children different?

- Normal vital signs vary with age;

- Blood book is relatively larger (lxxx-90ml/kg) than that of adults (65-70mls/kg);

- Blood volume is relatively smaller in accented terms (800mls in a ane-year-old);

- Children compensate for large intravascular losses (more than 30%) before becoming hypotensive.

- Chest-wall is more compliant than in the adult. Therefore major contusions or lacerations to the heart and lungs may occur in the absenteeism of rib fractures.

- Urine out-put is relatively greater (Child 1-2mls/kg/60 minutes; Developed 0.5mls/kg/hr)

Hypotension indicates that death is imminent.

Causes of circulatory compromise

- Respiratory failure/hypoxemia/hypercarbia;

- Claret loss - internal or external;

- Tension pneumothorax;

- Pericardial tamponade;

- Ruptured ventricle (rare);

- Cardiac contusions;

- Acidosis;

- Burns;

- Profound hypothermia.

Effects of circulatory compromise

- Decreased or complete loss of consciousness;

- Respiratory distress/failure;

- Hypovolaemia: - Reduced cardiac output leads to inadequate blood flow to all body organs (Hypovolaemic shock);

- Tissue hypoxia, metabolic acidosis and increased respiratory charge per unit;

- Ischaemic injury to the encephalon, heart, kidneys, liver, bowel with jail cell decease and inadequate function of these organs.

In all aspects of trauma management, the master survey is the first priority

Primary survey

Airway with c-spine stabilisation (encounter airway management section) Breathing (encounter breathing management section)

Circulation assessment and direction

Circulation assessment

Examine

Pulse

- Brachial artery in an baby, up to 1 year;

- Carotid artery in a child, 1 year or older

- Femoral artery

- Tachycardia - is a sign of shock, too as of fright and feet.

- Bradycardia - is a sign of imminent expiry.

- Pulse volume is reduced in shock

Capillary Refill

- Press on the sternum for five seconds then release and count the fourth dimension to reperfusion. Upward to 2 seconds is normal.

- Capillary refill is prolonged early in shock, but is also prolonged by pain, fever and environmental factors, such as cold.

- This is a sensitive sign, simply non specific, and should just be used in conjunction with other signs of shock.

Skin colour/temperature

- Mottling/pallor and cyanosis of the skin indicate poor perfusion due to either a sympathetic response to low cardiac output or to pain, fear or cold.

Claret Pressure

- Hypotension is a belatedly sign of shock, and imminent expiry.

Look for other signs of circulatory inadequacy

- Respiratory distress or failure;

- Agitation, confusion or decreased conscious level;

- Rapid, deep breathing may be a sign of metabolic acidosis

- Decreased urinary output.

Management of circulation

- Consider demand for chest compressions

- Ensure adequate vascular access

- Obtain claret specimens

- Assess and manage haemorrhage

- Fluid Resuscitation

- Drugs

- Re-assessment

Ensure adequate monitoring of saturations: cardiac monitor, finger on femoral pulse for pulse check.

If the pulse is abscent or less than 60 and there are no other signs of life: commence firsthand chest compressions and total cardiopulmonary resuscitation.

one. Breast compressions Babe <1 twelvemonth

| Landmark | i finger-breadth below inter-nipple line. |

| Technique | Two fingers depth i/iii of the AP diameter of the chest |

| Rate | 100 per minute |

Ratio of compressions to breaths: five:1

landmark infant

Pocket-sized Child <8 years

| Landmark | ane finger breadth higher up the xiphisterum |

| Technique | Heel of one hand - depth ane/3 of the AP diameter of the |

| Charge per unit | 100 per infinitesimal |

Ratio of compressions to breaths 5:1

Larger kid

Landmark Two fingers above the xiphisterum Technique 2 hands overlaid (as in adults) Charge per unit 100 per minute Ratio of compressions to breaths 15:two

2. Ensure adequate vascular access

- At least ii large-diameter cannulae.

- If unable to obtain access in 90 secs, insertion of an intra-osseous needle is recommended.

- If experienced in advanced vascular access, consider inserting a large-bore, rapid-infusion canula into the femoral, internal jugular or subclavian where major ongoing claret loss.

- Venous cut down. Apply merely as a final resort.

Sites of venous admission

- Medial antecubital fossa at the elbow.

- Long saphenous vein at the ankle.

- Cephalic vein higher in the upper arm.

- Back of hand and foot; use in an infant when it has non been possible to cannulate a larger vein. Usually a Size 22G cannula can exist inserted. This may be sufficient for initial volume expansion, simply will be insufficient in older children, if there is ongoing haemorrhage or a poor response to the initial fluid bolus.

- Intra-osseous. In a child with established shock, if venous admission cannot be gained within 90 seconds, insertion of an intra-osseus needle is recommended (Run across chapter 2).

- Femoral vein if skilled, and there is no severe intra-abdominal or pelvic haemorrhage.

3. Obtain blood specimens for:

- FBC,

- Blood saccharide

- Cantankerous-Friction match (minimal requirements): -Baby 2 units -Child 4 units -Big kid 6 units

4. Assess and manage bleeding

Control bleeding:

- External: Cess of blood loss (at the scene, in the linen, on the floor). Think the scalp, which tin exist a major source of blood loss in children. Most external haemorrhage in children tin be controlled with straight pressure. Employ of focal pressure with express dressings is more likely to control bleeding than large bandages. Where extremity haemorrhage cannot be controlled with directly force per unit area, a tourniquet may be helpful.

- Internal: Breast and abdomen bleeding may require surgical intervention in order to attain control.

Splint and stabilise fractures.

- Pelvic fractures may cause significant claret loss, and a binder to the pelvis may essentially reduce this. A sheet or towel wrapped tightly around the entire pelvis may stabilise the bleeding.

- Later definitive control in theatre - where advisable.

5. Fluid Resuscitation

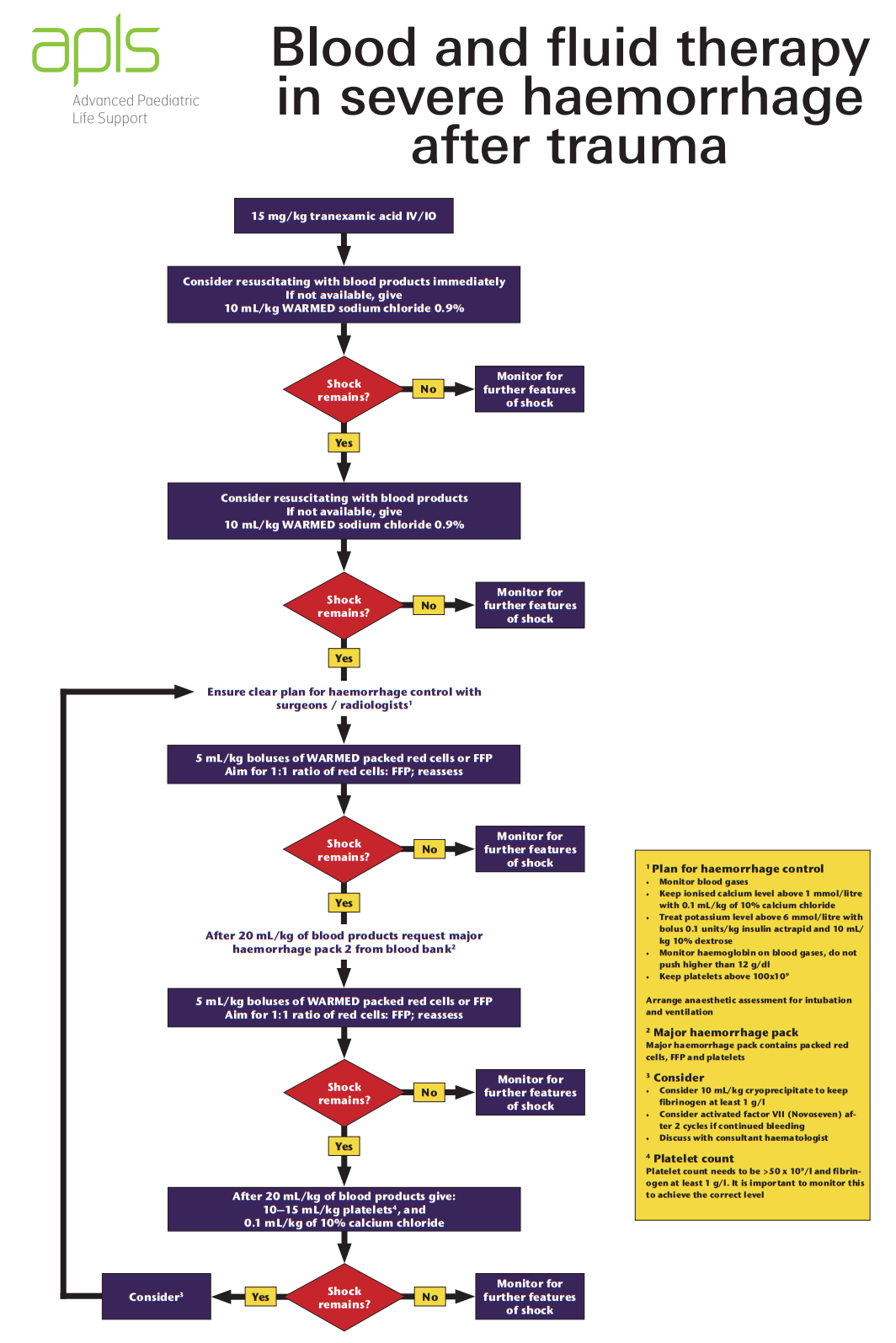

Look for any signs of circulatory compromise, as in a higher place. If nowadays consider fluid resuscitation with blood equally per your own institution protocol, or as per the APLS algorithm below:

Obtain anURGENT SURGICAL REVIEW if there has been inadequate response to the first two fluid boluses.

Reassess: Hour, capillary refill, and other signs of circulatory adequacy.

If the circulatory signs are deteriorating and non responding to fluid bolus, consider whether there is:

- Presence of on-going internal bleeding;

- Tension pneumothorax;

- Haemothorax;

- Haemopericardium;

- Spinal cord injury (low blood pressure, warm pare, slow center rate, no limb movement, patulous anus).

In hypovolaemia, fluids will demand to exist infused rapidly.

This requires:

- 50 ml bolus via syringe for small volumes and pocket-size children;

- Rapid infusion catheters, if available;

- Blood pump sets;

- Pressure bags;

- Blood warmers.

6. Inotropic support

Injured patients usually require replacement of volume rather than use of inotropes. Consider give-and-take with a paediatric intensive care physician if you consider your patient requires inotropic support.

7. After cess: re-cess

Repeat Primary Survey and go on monitoring vital signs, saturation, witting state and urine out-put.

Specific management bug of circulation

- Burns (see burns / direction of burn down wounds clinical practise guideline)

- Head injury (encounter caput injury section)

- Cardiac tamponade (run across chest injury section)

- Myocardial contusions (meet chest injury section)

- Pneumothorax (see chest injury section)

- Haemothorax (come across chest injury department)

Suggesting reading list

- Advanced Paediatric Life Back up. 6th ed. John Wiley & Sons, 2017

- Fleisher G, Ludwig S (eds): Textbook of Pediatric Emergency Medicine (4th ed). Philadelphia: Lippincott 2000. Capacity i (Resuscitation: pediatric bones and advanced life back up); 10 (Cardia emergencies); 104 (Major trauma); 3 (Stupor);.

- Bersten A, Soni North (eds): Oh's Intensive Care Manual (5th ed) London: Butterworth Heinemann 2003.

- Macnab a, Macrae D, Henning R (eds): Intendance of the critically ill child. London: Churchill Livingstone 1999.

Source: https://www.rch.org.au/trauma-service/manual/circulation-management/

Posted by: richiesalmor1959.blogspot.com

0 Response to "Which Assessment Finding Indicates That The Infant Has Hypotensive Shock"

Post a Comment